Calling down the lightning

Posted: January 16, 2026 Filed under: Art, Coding, Creations, DIY, Explorations, How-to, That Totally Worked | Tags: arduino, attiny, blinky, burning man, DIY, electronics, fastled, Halloween, LED, LEDs, light, lightning, MOSFETs 2 CommentsSo here was the big idea: a bunch of umbrellas with lightning in them. Like this:

Sianna and Dean and I started brainstorming about this as an idea for an art project for Burning Man 2018, and as these things do, the idea quickly blew up from a simple idea to include all kinds of complicated and awesome details.

The original idea was something like:

- umbrellas

- plain, always-on LED strings (cool white) sewn into the umbrellas

- use the pre-wired 3xAA battery pack that comes with the LED strings

Here’s where we wound up after a bunch of brainstorming:

- umbrellas

- four independent strings of LEDs (cool white) sewn into each umbrella, so that there could be animation and motion

- microcontroller programming of the LED strings, to create the flashes and motion

- some other sort of battery setup, not just the plain 3xAA battery pack that came with each LED string

- synchronization of the whole pack of umbrellas together, so that lightning could flash across all of the umbrellas at once, or across them in some kind of fast sequence

Sianna and Dean did all the sewing of the LEDs into the umbrellas, and I did the electronics design, construction, and programming.

What follows is the story of how I arrived at the final electronics design for these “stormbrellas”. I started with an initial electronics design for each umbrella that required some kind of full Arduino board plus a custom PCB ‘shield’ with a literally a dozen discrete components on each board to drive the LED strings. Then, through some outside-the-box thinking, some semi-careful / semi-brave experimentation, and progressive refinement I wound up with a design that required a total of just three discrete components to control each umbrella — and no “Arduino” board.

I am not a big expert at this sort of electronic design project, so a great deal of this was new territory for me. I’m hoping that you find this story interesting, and that perhaps it inspires you to try something new in this area, as well.

The Naive Design

The LED strings that we were using were the kind with ‘grain-of-rice’ LEDs mounted on barely-insulated bare metal wire, like this.

I wanted to use an Arduino (of some sort) to control the strings of LEDs, because I know it pretty well, and I already had a bunch of them lying around waiting to be used in projects.

Power to the pixels

I know that you can power individual LEDs directly from the ‘output’ pins of an Arduino, by connecting the LED from the output pin, through a (very important!) current-limiting resistor, to Ground. There’s a famous sort of joke in electronics that if you omit the current-limiting resistor, the LED will try to draw more power than it can handle, and in a very short period of time it will turn from a Light-Emitting Diode into a Smoke-Emitting Diode. (See also: “light-emitting resistors”.) So you always always always need to make sure the LEDs can’t draw more power than they can handle, and the way to do that is a current-limiting resistor.

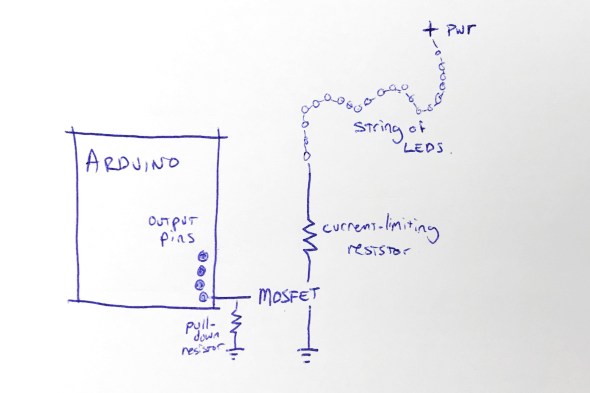

I also know that there’s a limit to how much current you can draw directly from one Arduino pin, and that you definitely cannot run a whole string of LEDs directly from an Arduino output pin. Instead, you need to use a power transistor, like a MOSFET, as a sort of a power switch. The Arduino controls the MOSFET, and the MOSFET switches the high-current power on and off to the LEDs. Each MOSFET needs a ‘pull-down resistor’ to turn it all the way off when it’s not being activated.

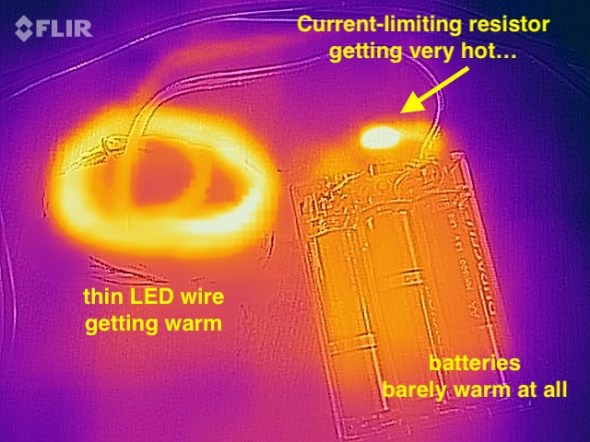

Of course each string of LEDs still needed a ‘current-limiting resistor’ as well. When I dissected one of the battery packs that came wired to the LED strings, I found that each one had 3xAA batteries (4.5 volts total), an on/off switch, and a 3.6 ohm current-limiting resistor, all in series with the string of LEDs. These particular LEDs seemed to want something like 3.3 volts across them. The battery pack (3xAA) produced 4.5v, and their simple design just used the small resistor to limit the current, and drop the voltage — throwing away the rest of the energy as heat. And wow did that resistor get hot!

I measured the temperature of the resistor (in open air) at over 140ºF when the LEDs were lit. It was definitely keeping the LED current and voltage down, but it was throwing away a whole lot of the battery power as heat, too. I estimated that nearly 1/3rd of the energy in the batteries was being turned into heat, and only about 2/3rds of the energy was coming out as light. Anyway, clearly the current-limiting resistor was important for these LED strings.

So I figured that I’d want an Arduino board, and then for each string of LEDs, a MOSFET, a pull-down resistor, and a current-limiting resistor, arranged something like this:

This shows the rough design for controlling one string of LEDs; to control four strings of LEDs, I’d need four MOSFETs, four pull-down resistors, and four current-limiting resistors. I figured that I’d mount all of that on some kind of Arduino ‘prototyping’ shield. Each shield would have those twelve components on it.

Call me lazy (go ahead, I’ll wait), but that seemed like a lot of parts, and a lot of work to build six umbrellas that way.

“Grandfather say ‘It never rain every day'”

I started thinking about those current-limiting resistors, and these LED strings, and about Burning Man, and about lightning itself. To simulate the look of lightning, I was not going to run these LED strings turned on all the time. In fact, they’d be turned off most of the time. I’d only need to power them up for short, bright flashes. And of course, this being Burning Man, the brighter, the better!

I also thought back to this great tech note from Cree (the superbright LED people) entitled “LED Electrical Overstress”, but which I refer to as “So You Want To Run Our LEDs Beyond Their Rated Power Limits”. http://www.cree.com/led-components/media/documents/XLamp_Elec_Overstress.pdf This tech note addresses the question “OK, so if the LED is rated for X volts, what actually happens if I run it at a voltage higher than X, but just for a short time?” And the answer they give is something like this: well, it might be a little bit brighter (but not proportionately), and it will probably also shorten the life of the LED, especially if the LED is over-volted for any significant amount of time.”

And I thought about those tiny little 3.6 ohm current-limiting resistors in the battery wired pack. I wondered if I needed them at all. Maybe I could sneak by without the current-limiting resistors — if I only pulsed the LEDs on for short flashes. And maybe, just maybe, the LEDs would flash brighter than usual, for those short flashes, if I omitted the current-limiting resistors. I decided to try it as an experiment: run the LED strings with no current-limiting resistor. Well, sort of. I say sort of because those LEDs are strung along very long, very skinny wires. And you know what a long, skinny wire acts like? Hint: a resistor.

Well, I tried running one of the LED strings for fifteen minutes solid, at full power, with no (external) current-limiting resistor and here’s what I found: the LED strings do light up a little bit brighter. The wires themselves definitely got warm, but not too hot to touch. I wouldn’t want to run them like that, full-on, for hours… but that’s not the plan. The plan is to flash them on for fractions of a second, or maybe even flicker for a couple of seconds, and then leave them off for a long stretch.

So I decided that since I was just flickering the LED strings on with (much) less than a 10% duty cycle, I could probably skip the current-limiting resistors … and get brighter flashes in return. Win-win.

And in addition to the specific component reduction (and brightness boost), this planted a seed in my head: sometimes you can go beyond the rated limits of a device, especially if you’re only doing it for a short time. Keep this in mind; it shows up again later.

Shifting away from MOSFETs

At this point the design for each umbrella is basically: Arduino + protoshield with four MOSFETS and four pull-down resistors. And of course four LED strings. I didn’t want to juggle the four separate MOSFETs, and I started wondering if there was some pre-packaged integrated circuit that basically had four MOSFETs inside it, so that I could reduce the part count from 4 MOSFETs down to one IC.

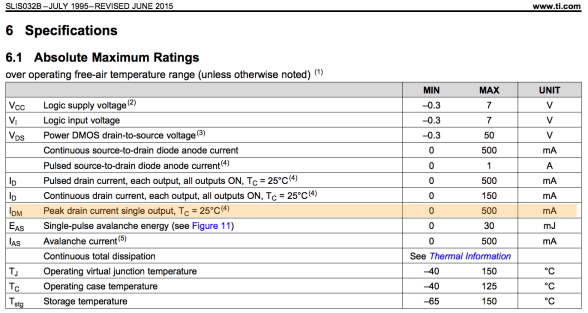

Looking around for a while, I came across the TPIC6B595, a “high power shift register”. They’re a bit like the popular 7HC595 shift register, with eight output pins, but they can drain “up to 150mA” per output pin. This might be the chip for me, I thought. But then, Hrm, I wondered, I wonder how much current I need for each LED string. I did some tests and found that each LED string could draw up to about 350mA. 350mA is far more than 150mA, so I didn’t think this chip was going work for me. On a lark, I decided to read the actual datasheet for the chip, from TI: http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/tpic6b595.pdf And look what we have here (highlighting is mine) …

While the continuous drain current is 150mA per output pin, the peak drain current per pin is 500mA! And 500mA is greater than the 350mA that I need to flash the LED strings on for a few instants! Maybe this was the chip for me after all. I ordered one to test. Well, I actually ordered two, because electronics tend to not bounce back well from being tested with current levels above their ratings.

The chip arrived, and I wired it up, found some Arduino code to drive it, and lo and behold, it worked! In fact, I was able to hook up all four LED strings to the TPIC6B595 chip, and light them all up brightly (and briefly!) with no detectable overheating of the chip. I did note that the datasheet said that the whole chip could only handle one Amp (1000mA) of current. If I lit up all four LED strings at 350mA each, that would be 1400mA, more than the rated maximum current of the chip.

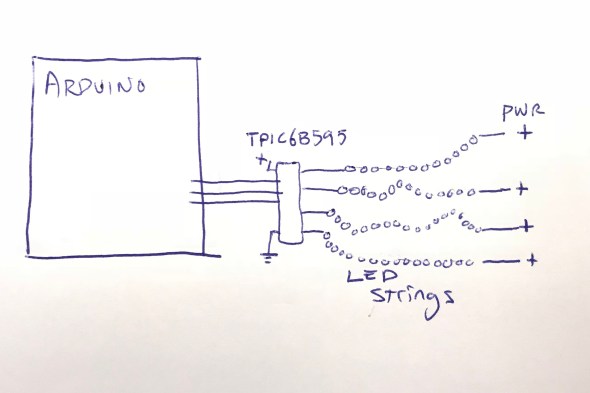

But again I wondered: OK, so it’s rated to handle 1000mA total. But what happens if I pulse 1400mA through it for one tenth (1/10th) of a second? Does it instantly blow up? Does it self-limit the current to 1000mA? Does it shut down and need to be powered off to reset it? Again, I decided to try it. The answer: it did not shut down, or need to be reset, or instantly blow up. In fact, it seemed perfectly happy to deliver 1400mA of current, as long as it was for short pulses, with cool-down periods between them. I decided to go forward with this, and see how far I could get. One chip, no discrete MOSFETs, and no pull-down resistors! If it worked, I liked this a lot.

Here’s where I was:

Flashdance (What A Feeling)

At this point I had a setup where I could drive all four LED strings from my Arduino code, as long as I didn’t run them all at full-blast all the time. In fact, I had to be mindful to keep the overall power level low, even if sometimes I spiked it up above the rated power level for TPIC6B595 chip, and above the standard continuous power level for the LED strings.

I spent a few hours studying ultra-slow-motion videos of lightning strikes, like this one:

After watching them over and over, I wrote and tested and refined some code that I thought created the same kind of visual impression, while also being mindful of the power envelope that I wanted to stay within. Once I had the code put together, I noticed that it was actually pretty small: compiled the code size was just about 3K, and it used less than 100 bytes of SRAM for global data. The small code and data size were hardly surprising in retrospect; in a sense, all that it did was flash four output values. I’d used FastLED’s math functions, which tend to be compact, including FastLED’s random number generator for the timing of the flashes. FastLED’s random number generator (well, pseudo-random number generator) is significantly more compact than the default Arduino random functions, which also helped reduce the code size.

The small code size started me thinking: if I only need this tiny program, and this tiny amount of data, maybe instead of a full-blown Arduino board, I could just get away with a ‘bare’ ATtiny85 microcontroller. I knew that people did that, but I’d never done it. Luckily, there’s good documentation about how to wire up an ATtiny for programming, and good Arduino IDE support. https://github.com/SpenceKonde/ATTinyCore I decided to give this a try. I ordered a few ATtiny85s ($2.80 each) and the required (0.1uF) decoupling capacitors ($0.22 each). I used a special $15 ATtiny programmer to help simplify the programming process; I wanted to streamline the exploration of the ATtiny85 option as much as possible for myself.

When the ATtiny85s arrived, it took me a little while to get it all figured out: burning the bootloader onto the chips, and then compiling and loading my code. My original code used the Arduino SPI library to communicate with the TPIC6B595, but the ATtiny85 doesn’t have a true SPI library, so I had to adapt my code (and my head) a little bit. Also, I had written an interrupt handler routine to provide PWM dimming of the LED strips, but my code had used the TimerOne library, which is not officially supported on the ATtiny85, so I had to find an ATtiny-patched version of the library and switch to use that. https://github.com/StoykoDimitrov/TimerOne Also, due to the slower clock speed (8MHz vs standard Arduino’s 16Mhz) I had to halve the interrupt rate that I was using for my PWM support. But eventually, I got it all breadboarded up and wired and programmed, and it worked!

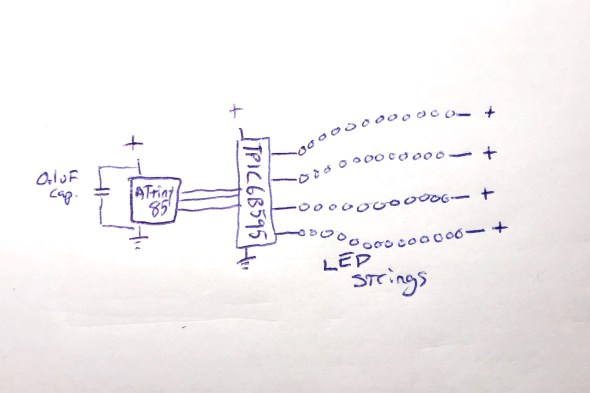

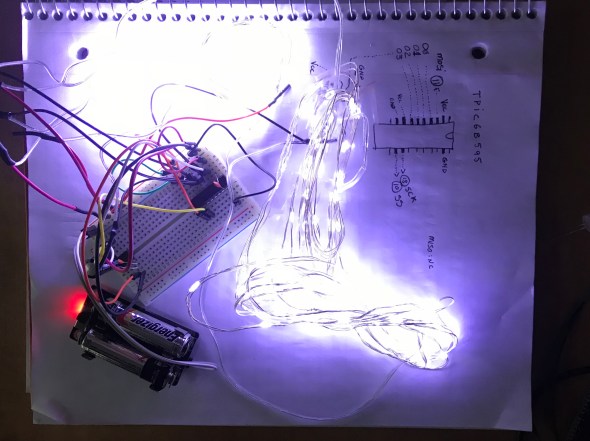

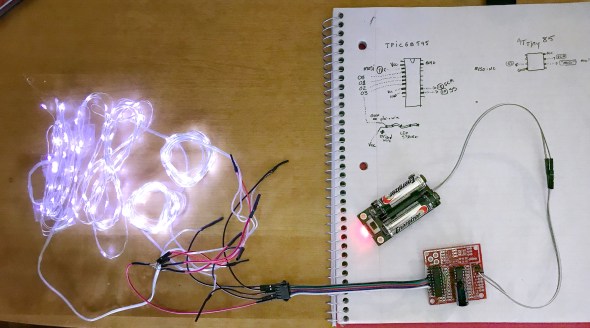

Here’s where I was at that point: no Arduino board, no loose MOSFETs, no pull-down resistors, no current-limiting resistors:

Everything worked great, until it didn’t

Everything worked great, even when I switched from a plug-in power supply to battery power… and then it started not working. It would start up fine, and ‘rumble’ some dim lights with no trouble, and even show the first few medium-bright lightning strikes. But on the fourth lightning strike, an extra-bright set of flashes, it would lock up. It always locked up on the fourth flash, which was always extra-bright, because the random number generator that the code used to sequence the ‘random’ flashes was, in fact, completely deterministic. Even though it might not seem that way to the casual observer, the same pattern of flashes always occurred, and the fourth one was always extra-bright, and that kept killing the microcontroller.

Based on my previous experience with battery-powered microcontroller-driven projects with lots of LEDs, I had a hunch, which turned out to be right: when the LEDs all flashed on brightly, the drain on the batteries from the bright LEDs caused an inverse voltage spike – a voltage dip. The voltage dipped too low, just for an instant, and the microcontroller locked up.

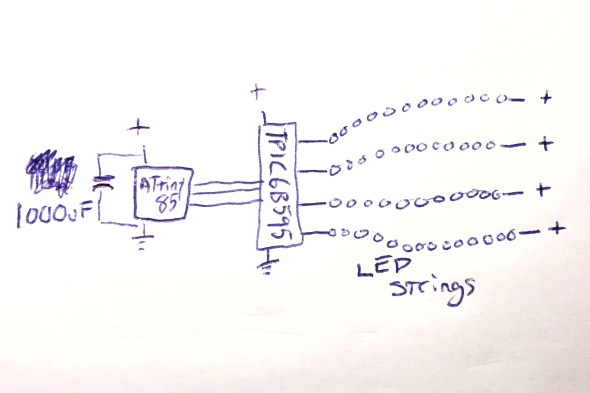

I thought about how I might isolate the microcontroller’s power from the sudden spike/dip from the LEDs flashing on full brightness. I could, of course, just reduce the maximum brightness of the LED strings, but this was a project for Burning Man, and I’m pretty sure that “reduce brightness” isn’t one of the ten principles. All I needed to do was power the microcontroller for a very short time, to bridge it across the dip caused by a very bright flash. I decided to try an experiment: I replaced the 0.1uF ‘decoupling’ capacitor ($0.22) next to the ATtiny85 with a capacitor with 10,000 times the power capacity: a 1000uF electrolytic capacitor ($1.22). My theory was that even when the LEDs spiked up in brightness, the new 1000uF capacitor would continue to provide just enough smooth power to the microcontroller it to keep running correctly. And it worked: even when bright flashes hit the LED strings, the microcontroller kept chugging along. Here’s where I was:

And this worked perfectly.

Now all I had to do was figure out how I was going to power this whole thing when it was mounted up inside an umbrella.

Hello Power My Old Friend

As I have written about before (see Cautionary Tales of Power), power is always a real pain in the grounding strap. Here were the choices that I was thinking about:

- 3xAA: this would be 4.5 volts on fresh batteries, and about 3.9 volts on ‘dead’ batteries. The microcontroller would probably work okay, and the LEDs would probably be okay, but I sort of felt like a 3xAA battery pack would be a little bit bulky and heavy. This was my ’emergency fallback’ plan.

- 4xAA: 6.0v on fresh batteries, 5.2v on ‘dead’ ones. I would have to use a voltage regulator, or a buck converter to drop the voltage down to the 4.5 – 5.0v range that I wanted. Plus a 4xAA battery pack would be even bulkier and heavier than the 3xAA pack above.

- Lithium Ion rechargeable battery pack: 3.7v when fully charged, 3.0v when empty. I’d probably want a boost converter to get up into the 4.5-5.0v range that I wanted. I love rechargeable batteries in general, but in the middle of the desert, there’s something to be said for being able to just eject a set of dead AAs, and drop in a fresh set. Using a lithium battery pack would make that much harder. Related options I thought about : standard 18650 cells, and also LiFePO4 cells.

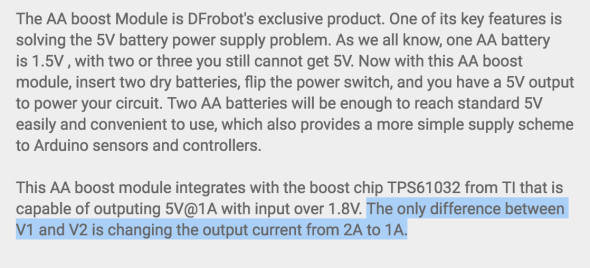

- 2xAA + boost converter: this was what I really wanted to do. I wanted to use the DFRobot “AA Boost” module, which holds two AA batteries (very firmly), has a built-in on/off switch, and a boost converter which produces 5v output. It even has a “low battery” warning LED. The whole module costs $5.90 in quantity 1, and I’ve used them many times very successfully. https://www.dfrobot.com/product-991.html

I already had some of these 2xAA+boost modules on hand, and was about ready to go forward with this plan when I spotted this in the DFRobot description. Note the current limit on the updated “V2” version of this module:

The maximum output current from this module was now just one amp. Not two, but one. One amp = 1000mA. And you may remember that the maximum power draw from the LED strings when they’re all fully lit, for a split second, is 1400mA total. And the 1400mA that we need is more than the maximum power that this module can provide.

Or… is it?

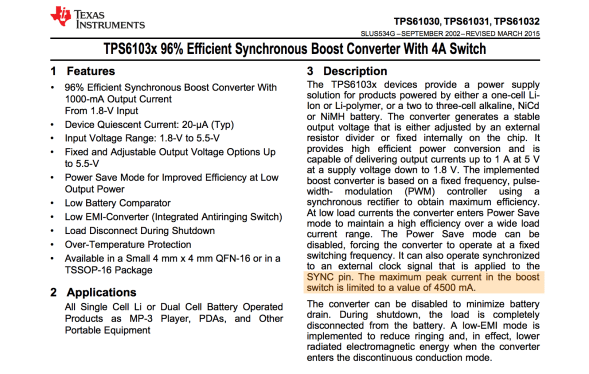

I looked up the TI TPS61032 boost chip that DFRobot uses in their boost module, and found the data sheet. http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/tps61032.pdf And while it definitely describes the chip as a “boost converter with 1000 mA current output”, look what it says in the highlighted (by me) portion of the datasheet:

And with that datasheet in hand, I decided to do the same thing that I’d done twice before on this project: try it, and see if the components can operate over and above their advertised ‘continuous’ ratings for brief periods, with cool-down rest periods between. And the answer? Yep, short bursts above the ‘continuous’ rating seemed to work fine!

I had had a battery-life goal for the umbrellas: I wanted them to be able to run, at Burning Man, from dusk to dawn (12 hours) on one set of AA batteries. Once I had the design all wired up with the DFRobot AA boost module, I popped in a fresh set of AAs, turned it on, and went to bed. Not only was it still running the next morning, it continued to run for over 48 hours continuously, and it might have run longer, but I had to get back to work on it, so I turned it off. Next I had to figure out what I was going to do about a circuit board.

The Chairman of the Board

I’ve never designed a custom printed circuit board before by myself, and I really wanted to do that for this project. Now that the total part count for each board was down to just three (the ATtiny85, the TPIC6B595, and the 1000uF capacitor!) it seemed like a great first project for me. However, time before Burning Man was getting a little tight, and I looked around for other options that might be faster and designing a custom board, and having it manufactured for me.

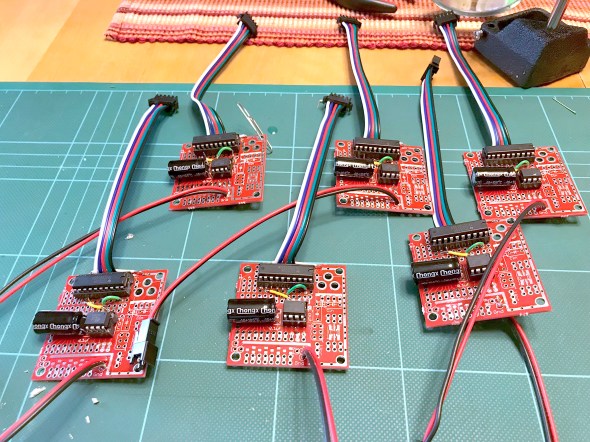

Over on Tindie, I found a great little ATtiny85 Project Board for $1.75. https://www.tindie.com/products/DrAzzy/attiny85-project-board/

These little boards had: space for the ATtiny85, space for the 20-pin DIP TPIC6B595, and even a spot for the capacitor. I picked up some of these boards, added sockets for the DIP chips, seven jumper wires to inter-connect the two chips together correctly, attached some multiconductor connectors for the LED strings and power, and poof! Just look at that neat, tidy little red board there!

With all this ready to go, Sianna, Dean, and I worked out how we wanted the LED strings attached to the five-pin connectors. Sianna and Dean worked madly and mightily sewing the lights into the umbrellas, while I went into production mode, and made five more complete sets of boards and battery packs. If we’d been making more than six boards, I would have done a custom PCB for sure. Getting all those jumper wires right was my least favorite part of this project, but eventually it started going faster, and then they were all done!

To this day, I’m still pretty proud of the three-component controller boards, and the development path that got me here.

Putting it all together

Sianna and Dean did a tremendous amount of work sewing all the LED strings into six large white umbrellas. When the first one was all put together, it was time for the first visual test. Full disclosure here: the umbrellas do not make thunder noises; the thunder noises in the following two video clips were ‘added in post’. We had thought about what it would take to make really good thunder noises, and the short answer was: a really big power supply (read: a heavy battery) and a really big (read: heavy) speaker — neither of which was going to integrate well with a umbrella intended to be carried in one hand. So: no audio. You just have to imagine the thunder noises, or, in this case, you can listen to the ones I dubbed into the video.

So here was Stormbrella #1, sitting on the couch.

And then came the whole collection, Stormbrellas #1 through #6, scattered across the living room.

For reasons of time and technology, the six of them are not wirelessly synchronized with each other, but other than that, these were just what we hoped. Sianna and Dean took a bunch of them out to Burning Man, where the umbrellas flashed their lightning, and fought mightily with the high winds in the Black Rock desert. Some of the stormbrellas even lived to return home and tell the tale of their adventures, and their victory.

Epilogue: A Halloween Thunderstorm

For Halloween, the kiddo and I always liked to decorate the front yard of our house with a big theme, like turning the house into a castle, or a discotheque, or an aquarium. And that year, we made the front yard into a thunderstorm. We set up a big sound system to play thunder, programmed flash strobes to light up the front of the whole house, and all of the stormbrellas on stands, giving lightning and umbrella vibes at the same time. Also I put a sprinkler on top of the house so that it was actually raining the tiniest bit, completely with a baffle to keep the actual front walkway up to the house — and the trick-or-treaters — dry. The overall immersive effect was great, and the stormbrellas rode again!

I still have the stormbrellas, and sometimes when it’s a rainy night out, I carry one of them as I walk, happy and dry underneath as the lightning I made flashes overhead.

Easter Egg Hunt 2017

Posted: April 17, 2017 Filed under: Creations, DIY, Explorations, Getting A Clue, That Totally Worked, Uncategorized | Tags: chocolate, colors, Easter, easter egg hunt, easter eggs, fonts, logic, puzzle, puzzle hunt, puzzles 2 CommentsOh, we love our Easter Egg hunts.

Oh, we love our Easter Egg hunts. As the girls (now age 14) have grown from little kids, to tweens, to actual teenagers, what started as a simple find-the-hidden-eggs game has grown right along side them; it’s now a full-on multi-stage puzzle hunt. 2014’s hunt involved complex interlocking rules. 2016’s hunt involved cryptography and QR codes. Now, here’s how 2017’s puzzle unfolded…

Simple

The rules were simple: each girl would be assigned a couple of colors, and each girl could pick up any egg she found once she was certain that the egg matched one of her colors. Easy, right? Further ‘simplifying’ things, I announced that I had placed one giant colored egg on a pedestal with each girl’s name (and one for the parents), so all they had to do was look at the pedestal with their name, and they’d see their first egg color. I showed them all a picture (below) of how nicely I had set it up, and how easy it was going to be.

But when we got outside to start collecting eggs… quelle surprise! The wind seemed to have blown the eggs off their pedestals! How ever would the girls know which color was theirs??

Luckily, each pedestal contained a set of instructions for figuring things out in case of just such an emergency:

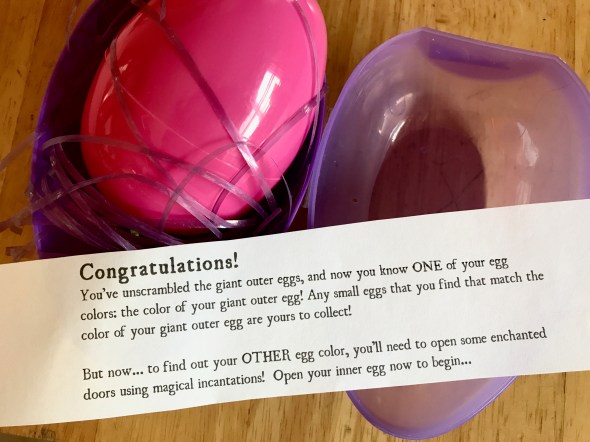

The girls retreated to the kitchen to pencil-and-paper this problem. After a few minutes, they’d worked it out with Rebecca offering supportive coaching (but not giving away the answers even though she’s great at these puzzles). The girls hastened outside to each crack open their correct-color giant eggs.

Inside each giant egg was a message… and another, smaller egg.

Inside the smaller eggs was some chocolate, which was immediate consumed as much-needed brain fuel. And there were also some scraps of cut up paper with writing across them — clearly they needed to be reassembled. The girls hurried back inside, and taped the paper back together, revealing four trivia questions about opening magical doors. (Full credit here: Three of these riddles were written by Ryan O’Boyle for Veracode Hackathon 10 & 5/7ths. His riddles were great, and inspired me to add one additional one of my own.)

It just so happened that the team included a Tolkien expert (Norm), and several Harry Potter fans (everyone but me) so the answers were quickly found. Bonus points to Abby for remember the spell “Alohomora”, and to Eleanor for remembering that the Ministry of Magic’s phone booth code was “M A G I C” on the telephone dial — and then using the Phone app on her iPhone to look up what numbers that was.

But now what? The girls still needed to know what colors of eggs they each were looking for, and all they had were these trivia answers — definitely not colors. Well luckily the third giant egg, the one for the parents, contained a “Helpful, Quick, and Easy Egg Color Key!” with some hand-wavey formula clues on it about how to transform the trivia question answers into numbers.

By considering a=1, b=2, etc., and adding up the letters in each trivial answer (and after I fixed a typo..oops), the girls arrived at numeric values… but still no colors. It was more or less at this point that Eleanor started invoking the word “patricide” in her running commentary.

Working through the formulas provided on the key, the girls had figured out that the variables k=112, j=250, x=147, and y=248, so, again, they had some numbers, but no colors. The key said that one color was y,y,x and the other color was k,j,k.

“But how are those colors?”, Rebecca asked, and there was a moment of silence.

“HEX CODES!” Eleanor exclaimed, and the chase was back on! Using an Internet color code converter, the girls converted 248,248,147 into yellow, and 112,250,112 into green. Colors at last!

Now with each of the girls knowing exactly which egg colors were theirs, they scooted out to the yard. Within just a few minutes, they’d found all of the (poorly) hidden eggs, collected them, and returned to the kitchen inside to savor the chocolate goodies within.

Then came the screams.

Then came the screams. For inside each egg not only was there a tasty bit of chocolate, but also… more sliced up message fragments. There was clearly another part of the puzzle. Madly, the girls sorted out all the pieces and assembled them:

The team stared at this for a while, and then started discussing the fonts: Papyrus, then a font that no one knew the name of, then Times, Comic Sans, and Helvetica (with a quick argument about Arial… ending with “Well, young lady, in this house, we use Helvetica!”). Could the five-letter word that the clue was asking for be made from the initials of the fonts? P_TCH? PATCH was considered for a minute, but when the girls hit on PITCH, the hints about “pining”, “note”, and “curveball” all clicked!

Using PITCH, they completed the partial URL and typed in http://tinyurl.com/2017EGGPITCH What came up at that URL was a photograph of the front of the house, with a big green arrow.

The girls practically flew out the front door, flipped over the flowerpot in the picture, and were rewarded with a glass jar filled with glittery treasure eggs, yet more chocolate, and a note saying VICTORY! CONGRATULATIONS on SOLVING the 2017 Easter Egg Hunt!

Happy congratulations were shared all around, and everyone enjoyed some of their hard-won chocolate.

With the puzzles finally solved, and chocolate fully secured, Eleanor finally stopped repeating the word “patricide” over and over, which she’d started saying nearly an hour before.

For the record, the total elapsed time was 56 minutes, 42 seconds — including the time it took for me to fix the typo in the math key (oops), and the time that Eleanor spent repeating the word “patricide”.

Maybe next year I’ll start making the puzzles hard.

Easter Egg Hunt 2016.

Posted: March 27, 2016 Filed under: DIY, Explorations, That Totally Worked | Tags: code, codes, CTF, cypher, cyphers, Easter, easter egg hunt, easter eggs, emoji, puzzle, puzzle hunt, puzzles, QR code, QR codes, rules 1 CommentWe’ve always loved Easter egg hunts, but with the girls getting smarter, faster, and more wily every year, we’ve had to make the hunt more… challenging. Our previous Easter egg hunt had infuriatingly complex rules as to which girl got which color of egg. But with the girls in middle school now — actual teenagers — I knew that I was going to have to step up my game if I wanted the hunt to last more than just a few minutes. Inspired by some of my puzzle-crafting Veracode coworkers, I put together our 2016 Easter Egg Hunt. Here’s how it went.

Step 1. Read the rules.

Once again, Eleanor and Abby were each given a sheet of paper indicating which colors of eggs they should each pick up. Here are the ‘rules’ they were given for this year’s egg hunt:

After a few false starts, the girls cracked the emoji substitution cypher. Since some symbols like🌀 and 👻 appeared only once on the page, it took some thinking to decode the whole set of color rules, but working together they did it.

Step 2. Find the eggs.

List of colors in hand, they ran outside to start finding the eggs hidden around the back yard. Each girl found all of their eggs within about ten minutes; finding the eggs themselves isn’t too terribly difficult — which is why we got into all these rules and colors and puzzles in the first place.

Step 3. Open the eggs… and wait, what’s this?

Once back inside, the girls opened the plastic Easter eggs… but wait! Where’s the loot?!? Instead of treats or trinkets, each egg held one small, oddly-shaped piece of paper with black and white squares on it: a QR code, cut into puzzle pieces.

Working quickly, the girls each assembled the pieces of their respective QR code puzzles. One went together easily, the other took some collaboration and a couple of different attempts before it all came together.

Step 4. Follow the clues.

Each girl’s QR code was different, and scanning the re-assembled QR codes led to two different URLs: two different tweets, by two different people (neither was me). Each tweet had a picture and a big clue about a different location around our house.

Step 5. Victory!

Eleanor dug down into our pile of birdhouses (why we have a pile of birdhouses is a long story for another day), and Abby popped open the lid of the grill. Each girl found a set of colored ‘crystal’ eggs — filled with sweet, sweet victory loot!

In just under 45 minutes, the girls had cracked a cypher, found the hidden Easter eggs, reassembled the QR code puzzles, and followed the twitter URL picture clues to find their well-deserved treasure. The chocolate was sweet, but from the looks on their faces, I think the taste of victory was even sweeter.

Now about next year…

First light – five years later

Posted: March 25, 2016 Filed under: Art, DIY, Explorations, Getting A Clue, Pearls of Folksy Wisdom, Reflections, That Totally Worked | Tags: art, blinky, fastled, journey, learning, LEDs, light Leave a commentFive years ago today I got my very first piece of LED art gear to light up for the very first time.

It was a Color Kinetics panel that you sent data to over ethernet, not an addressable LED strip & embedded microcontroller coding situation at all. The panel itself previously belonged to an LED art pioneer, “Frostbyte”, who had taken it with him on his desert adventures before his untimely and accidental demise. His old electronic gear was auctioned for charity, and without really knowing what I was getting in to, I bought this massive (28 pound!) metal box with 144 RGB LEDs in it, and the network controller to match.

I could find no open source software to drive it, and owning the commercial sequencing/design package was out of my reach. For three years, the panel sat in my workroom idle and dark. But at some point, I found that the vendor had a simple free “test program” available, and I decided to see what I could do. Since the color data was sent from the test program to the panel over ethernet, I was able to capture the network packets, reverse engineer them, write my own code to talk directly to the LED panel, and TA-DA! First light!

But even with that one LED panel up and running, more than a year passed before I started learning how to use addressible LED strips and Arduino microcontrollers. Another year after that, I had officially become ‘part of’ FastLED with Daniel Garcia.

And now? Now I’ve created LED art myself, taken it on my adventures– desert and elsewhere, sold it and gifted it. I’ve taught LED classes, and I’ve helped build an online community for thousands of FastLED users. I’m not sure what I expected when I first bought that LED panel, but I don’t think it was all this great stuff.

So if there’s a lesson here, it might be this: If something intrigues you, step toward it. You never know exactly where you’ll wind up, but the journey will be an adventure in the right direction.

Cautionary Tales of Power

Posted: November 27, 2015 Filed under: Coding, Creations, DIY, Explorations, Getting A Clue, How-to, Pearls of Folksy Wisdom, So that didn't work | Tags: arduino, blinky, DIY, fastled, fire, glow, glowy, LED, LEDs, light, power 3 CommentsWhen doing an LED electronics project, there seem to be three big “P”s that have to be tackled:

1. Pixels (which ones, how many, what configuration?),

2. Programming (what do I want, and how can I do that?), and

3. Power (how much, from where, and how do I distribute it?)

And people (by which I mean: perpetual newbies like me) tend to do them in that order: first wire up some pixels, then program them, then figure out how to power it all for real.

And of course, this often leads to a problem where you get stuck between steps 2 and 3, where you have your creation sort of up and running on the lab bench — but now there’s this little problem of how to power it, and you have to go back and rethink and rework other parts of the project to accommodate the power situation. So it’s worth planning for power from the start — which is easy to say, but hard to do!

What could possibly go wrong? (A list)

So what happens if you don’t plan for power? Well, here are some power problems that I have personally had. How many of these can you diagnose just from the description? (“Failure to plan” is a nice catch-all phrase here if you get stuck.)

- Hrm, now how do I get power all the way up there?

- Gee, that’s a long run of wire… but if I use fat wire, it’ll be expensive and heavy and cumbersome. Nah…

- I’ll use skinny wire, it’s much cheaper… Hey, why is it only reading 4v at the far end? And does anyone smell something burning?

- OK, I switched to thicker wire, and I’ll just re-use the power connectors from before. Holy cow now the connectors are getting hot!

- Fine, I’ll switch to these big thick nonpolarized connectors. Huh, that’s odd, it’s not working now. Does anyone smell something burning?

- For this other wearable project, I’ll use a simple battery holder and regular alkaline batteries… hey… why are the colors so ‘warm’.. no blue? And now no green, too…

- OK, switching power to one of those ’emergency phone chargers’ that takes AAs and puts out 5v from a USB socket. Hey! Why are the batteries dying so fast?

- OK, fine, I’ll switch to this lithium battery pack… hey, it said 5000mAh… so why did it stop powering my 5000ma project after only half an hour?

- How come my WS2811 project works fine from my computer, but then flickers like crazy when I power it from this cheap USB wall power adapter?

- For this big outdoor project, I’ll use this big, burly 12V lead-acid marine battery. Hey… how come it won’t hold a full charge after the first time I let the lights go all night?

- Everything was working fine yesterday, before last night’s rain!

- Everything was working fine yesterday in the cold and snow, so it should be working fine today now that it’s warming up, right?!

- I think I’m going to switch microcontrollers. The old one had a power regulator that could handle 12v input. Hey… do you smell something burning?

- Why is this power switch getting hot now? And why is it now totally stuck in the “on” position? And … do you smell something burning… again?

So: Plan For Power.

The lesson to learn here is that for basically any real project, calculate and plan the power first. Before you wire up any pixels. Before you write any code. Just stop for a minute and think about how much power you’re going to need, and where it has to come from, and where it has to go.

Use on-line calculators that will help you figure out how much power you’re going to need, and what gauge wire you’ll have to use given how long your cable runs are going to be. I also really like the “LEDstimator” app for iOS to help explore some “what-if” values for things like wire gauge. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/ledstimator/id945794010?mt=8

And above all else… uh… wait… do you smell something burning?

FastLED for the Apple II: Hack to the Future!

Posted: February 16, 2015 Filed under: Art, Coding, Creations, DIY, Explorations, That Totally Worked, Uncategorized | Tags: APA102, Apple, Apple //e, Apple II, AppleII, arduino, art, blinky, CALL -151, DIY, DotStar, fastled, glow, glowy, LED, LEDs, light, LPD8806, retrocomputing, WS2801 6 CommentsThese days, I hack LEDs. I’m the co-author (with Daniel Garcia) of the FastLED library for driving tons of high speed LED pixels and strips using microcontrollers like Arduino and Teensy.

But back in the day, I hacked a lot of Apple II. I published a couple of shoot-em-up games (with Geoffrey Engelstein), all written in lovingly hand-crafted 6502 assembly language.

Finally I decided it was time to link the present to the past: to connect a hundred high-speed RGB LEDs to an Apple II, somehow, and ‘port’ our FastLED library to 6502 assembly language.

Well, I did it, and it works. My new creation, “FastLED6502”, can drive a hundred 24-bit RGB pixels at more than 30 frames per second from an Apple //e :

The Details

Here are the details of “FastLED6502”:

- “FastLED6502” is a lightweight port of FastLED’s core functions to 6502 assembly language for the Apple ][, Apple ][+, Apple //e, and Apple //gs.

- Supports APA102 / Adafruit DotStar LED strips, as well as LPD8806 and WS2801 (though those two are not fully tested yet).

- The LED strip is connected to the Apple II using the 16-pin DIP game port on the computer’s motherboard. The 9-pin DB joystick/mouse port on the back of the //c, //c+, and //gs cannot be used, as it lacks the TTL digital output signals needed to drive the LED strip.

- 24-bit FastLED Rainbow colors are included, along with FillRainbow, Random8 and a number of other useful functions from FastLED’s main library.

- Everything had to be re-written from scratch in 6502 assembly language. Luckily(?), I still remember how to do that.

- The assembly code knows the binary serial protocols for the APA102 (Adafruit DotStar), LPD8806, and WS2801 LED driver chips. Depending on which one you select, FastLED6502 transmits the LED colors in the correct protocol over the game port TTL digital output lines.

-

Considering that the Apple II sports a 1MHz 6502 so slow that even a “NOP” takestwo cycles, overall performance is pretty good: more than 30 frames per second for a 100-pixel strip.

-

Speaking of speed, or lack thereof, “three-wire” clockless LED strips such as the WS2811 NeoPixel are not supported now, nor will they ever be. The CPU is would need to be at least 20X faster to support them, and it isn’t. For that you want an Arduino or Teensy, and FastLED proper: http://fastled.io/

FastLED6502 at Veracode Hackathon 7

How’s it work?

So how does this all work? Well, you connect the CLOCK and DATA_IN pins from the LED strip to a couple of pins on your Apple II’s DIP game connector port, add power, and you’re ready to go. The Apple II’s game connector not only has inputs for joysticks, paddles, buttons, and so on, but it also has a few digital outputs — and that’s what FastLED6502 uses to deliver signals to the LED strip. On all the 16-pin DIP Apple II game ports (except for the //gs!), there’s even one pin that delivers a super-fast digital pulse; pin 5 is the C040STROBE line, which can pulse twice as fast as the other digital outputs. If you choose that for your CLOCK pin, the FastLED6502 code automatically shifts into high gear, and you get faster performance. FastLED proper does this, too, in a much fancier way; it’s amusing that ‘little’ FastLED6502 does some of this, too.

The Code

https://github.com/FastLED/FastLED/blob/FastLED3.1/extras/FastLED6502.s65And here’s the RainbowDemo.s65, as shown in video:

https://github.com/FastLED/FastLED/blob/FastLED3.1/extras/RainbowDemo.s65

This is Crazy

Lanyard-mountable LED throwies

Posted: May 25, 2014 Filed under: DIY, Explorations, How-to, That Totally Worked, Uncategorized | Tags: blinky, DIY, glow, glowy, invention, inventions, LED, LEDs, light, throwies, toys Leave a commentAt the last “HacKidThon”, we showed a passel of kids how to make LED “throwies”. Each one is a nothing more than an LED, a coin cell battery, and a magnet so the contraption can stick to metal surfaces, walls and buildings, and hang there glowing.

This week, someone asked me if we could modify the classic design somehow so that the LEDs could be attached to lanyards, instead of magnets. We wanted it to be as cheap and easy as the rest of the “throwie” recipe.

A little brainstorming with Eleanor, and we came up with this: plastic-coated paperclips!

The paperclips actually help hold the LED leads in place; we put tape around them as usual, though that’s not shown in the picture. The plastic coating keeps the paperclip from shorting out the positive and negative battery terminals.

The coated paperclips cost less than a penny apiece, and come in colors that match the LEDs. Victory!

Fire2012: an open source fire simulation for Arduino and LEDs

Posted: April 4, 2014 Filed under: Art, Coding, Creations, DIY, Explorations, How-to, That Totally Worked | Tags: arduino, art, blinky, DIY, fastled, fiery, fire, glow, glowy, LED, LEDs, light 3 CommentsI’ve built and programmed a couple of different ‘fire’ simulations for Arduino and LEDs, and I’ve had numerous requests over the years to share the source code. I’ve always been happy to share my work; the holdup has been that before I share my code for the world to peer at, I like to clean it up a little. I like to give the code a clean shave and scrub under its fingernails before it steps out onto the wide open Internet where it might have an audience with Her Royal Majesty, The Queen of England. It could happen.

Anyway, I finally cleaned up the code for one of my simplest and most legible ‘fire’ simulations, and I give it to you, your Majesty, and everyone else, too. Here’s a video of the code in action on a 30-pixel strip of WS2812B LEDs (or maybe WS2811) and an Arduino. Source code link is below the video.

Full source code is here: http://pastebin.com/xYEpxqgq The simulation itself is only about 25 or 30 lines of code. It uses our (open source) FastLED library to drive the LEDs.

Discussion about the code and how to port it and use it are here on the FastLED discussion group on G+ https://plus.google.com/112916219338292742137/posts/BZhXE4cqEN4

Enjoy!

-Mark

Running 2 Amps of LEDs through an Arduino Nano

Posted: February 25, 2014 Filed under: Coding, DIY, How-to, That Totally Worked | Tags: amps, arduino, blinky, fastled, hack, hacks, LED, LEDs, nano, power, USB 2 CommentsThe Arduino Nano provides up to 0.5 Amps of regulated +5v output, on it’s “+5V” pin, which can drive between 10-30 addressable LEDs, depending on your chosen brightness and animation patterns. Even if you connect a 2 Amp USB power supply (e.g. an iPad charger), the Nano’s little voltage regulator will overheat if you try to draw more than 0.5 Amps from the “+5V” pin on the Arduino.

However, you can ‘tap’ the pre-voltage-regulator power traces on the Nano’s circuit board, and drive 2 Amps of LEDs (over 100) ‘through’ the Nano, and do it in a way that keeps your wiring simple. Basically, you can find the places on the Nano’s board where the raw USB power connections are exposed, and tap into them there.

WARNING!

MODIFY, MISUSE, AND DESTROY YOUR ARDUINO AT YOUR OWN RISK!

DANGER! FIRE! RUN!

But, OK, if you wish to continue…

1. Flip the Nano over so you’re looking at the bottom side.

2. The unfiltered, unregulated +5 signal from the USB port is available on the board near the base of the D2 pin. Carefully solder a wire (red, for +5v) directly to the exposed component pin on the circuit board.

3. A convenient companion GND connection can found on the center pin of the power regulator itself. Solder a wire (black, for ground) to this pin.

4. By powering your LEDs from these direct-power traces (and thus directly from the USB power source), instead of through the Nano’s half-amp-max voltage regulator, you can drive up to about two Amps worth of LEDs, provided that you plug the Nano into a 2 Amp USB power adapter.

I’ve used this technique in probably six or eight Arduino Nano projects, and nothing’s caught fire (yet). With a little probing around, you can also find similar ‘hacks’ for other models of Arduino, e.g., the Uno, Leonardo, etc., but since power is handled differently on each board, you’ll have to figure it out differently for each board design.

Good luck!

Hoop skirt — made with real hoops!

Posted: October 15, 2013 Filed under: Art, Creations, DIY, Explorations, How-to, That Totally Worked | Tags: costume, costuming, dress, duct tape, eak, eleanor, hoop, hoop skirt, hula hoops, skirt Leave a commentEleanor and I spent this weekend working on her Halloween costume. Part of what she planned was a ‘hoop skirt’, but as you can imagine no commercially available hoop skirt met her exacting standards of design and quality — and also my exacting budgetary requirements. Naturally, we decided to take the DIY route! And, we pondered, what goes into a hoop skirt? HOOPS, obviously!

We picked up a used dress at The Garment District (our local vintage/costume/cheapo clothing mecca), a set of three hula-hoops, and some leopard-print duct tape. The smallest hula hoop became the bottom (largest) hoop for the skirt; the other two had to be dramatically resized smaller (via pliers, dremel, duct tape). We started construction from the waist down, with a nylon web belt with a parachute snap buckle. From there, we hung each hoop with repositionable blue painters tape, and balanced each one until it was level. Then Eleanor secured each hoop in place at the right height with duct tape.

And presto! A hoop skirt made with real hoops! (and duct tape, of course!)